In C.S. Lewis’ That Hideous Strength the modern world is on the cusp of a social and scientific breakthrough. The National Institute for Coordinated Experiments (NICE) is at the forefront of these scientific innovations, hailed by all the western world as the only organization able to cure every social, mental, and physical misalignment. It’s final goal is to create a new race of humans, one without sickness, ageing, or “backwards thinking”.

This book is one of Lewis’ least famous and seldom read because, I believe, of its tone. The story itself is very strange—Lewis Himself called it a “fairytale for grown-ups”—but the tone of the writing is deeply unsettling. It reads like a nightmare, beginning benign and ordinary to all appearances, but with an unsettling atmosphere of growing dread. The NICE is not just tampering with science and society in a neutral, godless vacuum—they’re whole operation is saturated in the supernatural though it is clothed in secular garb. It’s revealed that one of the main characters is a seer and can foretell what the NICE’s next move is. The head of the NICE turns out to be an actual reanimated head, supposedly brought back to life by scientific apparatus, but really inhabited by an malevolent spiritual power. It’s revealed that angelic forces which inhabit the outer planets are coming to earth to deal judgement on the NICE and even that the body of Merlin (yes…the wizard) has been resurrected and the main characters must find him and gain his trust before the NICE recruits him.

Why do I bring up this weird obscure book? For a couple reasons. Firstly, it’s worth mentioning that this book is only strange because it begins predicated on the assumption that it does not take place in a supernatural world. How could a story about a modern civic institution come anywhere close to a myth or fairytale? I love this book exactly for this reason. It exposes a fatal flaw in my thinking as a modern westerner which hopelessly inhibits my reading of the Bible. Buyenlarge, today we don’t genuinely believe that everything has Spiritual significance the way Scripture teaches.

In order to trace the Kingdom of God through Scripture, and on into history, it’s essential to notice this psychological handicap and intentionally work to disarm it. The world belongs to God and there is nothing in it He will not return to the influence of His will. “Behold, to the Lord your God belong heaven and the heaven of heavens, the earth with all that is in it.” (Deut. 10:14).

Secondly, I bring up That Hideous Strength because of its title. It’s taken from a poem by Sir David Lyndsay about the Tower of Babel; that is the root of Lewis’ story, and a deep and pervasive root it is. In the last chapter, I explained how the trees of life and the knowledge of good and evil have reflections at the center of every human heart—our wills either yielding to the influence of God’s will or our own human conception of what’s right and wrong. But the Bible doesn’t explicitly use the two trees in Eden as it’s running metaphor. Scripture also doesn’t speak in the abstract, using explicit, systematic language about the nature of the human heart in relation to God. Rather, Scripture chooses to follow a narrative route, for reasons I established in the previous chapter regarding myth.

The drama of the development of the Kingdom of God is just that, a drama, written intentionally to be read in the genre it was written in. In Genesis 11 the organized system of human sin opposing God’s Kingdom is given a name: “Babel”. It maintains this moniker up to the very final pages of the canon, although sometimes adopting the fuller title, Babylon and in the gospels and most of the epistles going by, the world. It is, in fact, a hideous strength, a warped and ruined parody of God’s ordered rule. More than that, it has real strength, reordering the value placed on human lives and erecting a false hierarchy of power derived from God’s sovereignty and His divine assembly. The saga continues at the opening of Genesis 11.

The Kingdom of Giants

First, a little set dressing. The world remains a wasteland and not a garden. Adam and Eve were cast out of God’s life-giving presence so that they would no longer take of the fruit of the tree of life and live forever in a state of misery and opposition to God. They have kids and, in a way, begin to fulfill their human calling to be fruitful and multiply, subduing the earth even by the sweat of Adam’s brow (Gen. 3:19 cf. 1:28). But again, the two trees appear in the heart of Adam’s son Cain, who becomes jealous of his brother. It’s another temptation in the garden, except there’s no serpent whispering in Cain’s ear. Instead, we hear the voice of God exhorting Cain to listen to God’s knowledge of good and evil and not his own.

Then the Lord said to Cain, “Why are you angry? And why has your countenance fallen? If you do well, will not your countenance be lifted up? And if you do not do well, sin is crouching at the door; and its desire is for you, but you must master it.” (Gen. 4:6–7).

God shows Him a tree of life, offering Him a chance to choose the way which God knows to be right over the impulse to sin swelling in Cain’s mind. Cain doesn’t even give God a reply. In the very next verse he becomes the first person to take another’s life. Again, just like with Adam and Eve, God comes asking a question which He already knows the answer to, “Where is Abel your brother?”, and Cain denies the truth. So the ground becomes cursed again because of the innocent blood spilled on it and Cain is sent out again into the wilderness, this time away from his family. Out there he founds the first city, one built on bloodshed and oppression which he names Enoch. This city of murder becomes the seed of what is later to be referred to as Babylon, the antithesis of the tree of life.

The whole world becomes swallowed in vice, death, and suffering such that “every intention of the thoughts of his [mankind’s] heart was only evil continually” (Gen. 6:5). Often at this point we like to skip to Noah and glance over a certain element which is crucial to the narrative. As we established earlier, the Hebrew Scripture is clear that God was not alone when He created mankind. Around Him was a kind of pantheon of lesser gods, His “heavenly host”. These shared in the image of God as they were to be His imagers, or representatives, in heaven, imbued with authority. However, there are two fronts to the Fall—humanity, and the elohim given to watch over that humanity.

There’s a kind of heavenly rebellion which results in certain sons of God being banished to the earth (Gen. 6:2; Isa. 14:12; 2 Pet. 2:4). Here we see that the Scriptural view of evil is not a dichotomy against flesh and spirit—earth versus heaven—as it is in certain Helenistic philosophies, but both heaven and earth in rebellion against God. What results is the exponential explosion of death and oppression under the heels of the Nephilim—the malevolent god-kings of the primeval world.

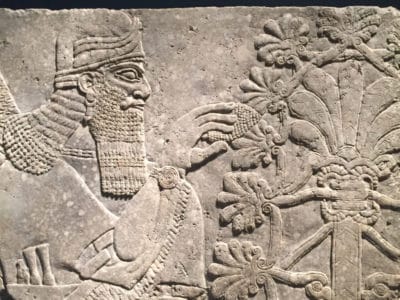

Don’t let this point throw you for a loop. The Nephilim are not such an intimidating hermeneutical hurdle when you have a clear grasp of their ancient near eastern context—which is the context of the book of Genesis. It’s impossible to do any scholarly research on the literary conception of the Nephilim without finding constant connections to Babylonian royalty. “Throughout Mesopotamian history, the legitimacy of kings was presented in terms of their closeness to the divine world in a number of ways: divine descent, divine favor, superhuman stature, or marriage to a goddess” (Daniel Snell). The idea of giant divine kings was contemporary in the ancient world, something biblical and deuterocanonical authors riff on continuously. The audience of Genesis would prick up their ears at the mention of giant god-kings on earth because that was exactly what pagan kings considered themselves. But while these kings considered themselves the harmonizing bridge between heaven and earth, Scripture sees through their propaganda and recognizes them as divine abominations.

More than being ancient Hebrew polemics, the Scripture’s language about the offspring of the sons of God has a typological element—a consistent, on-going metaphor.

The Nephilim, Anaqim, Rephaim, Emim, Zamzumim/Zuzim, some Gibborim, and other individuals (e.g., Goliath) can all be classified as “giants”—not only with respect to their height and other physical properties, but also with respect to the negative moral qualities assigned to giants in antiquity….through which we gain insight into central aspects of ancient Israel’s symbolic world. All that is overgrown or physically monstrous represents a connection to the primeval chaos that stands as a barrier to creation and right rule. (Peter Machinis).

The disordered chaos of the black, void sea, separated from God in the beginning of creation, is echoed in the arrival of these forefathers of Babylonian kings. The order which God intended for the cosmos is reflected in His chain of command: first Himself, then his divine assembly as agents of His will toward mankind, and then His human imagers on earth. It’s up for debate whether it was inherently wrong for the sons of God to manifest themselves on the earth, but what they do with that power shows us the state of the universe at this point in time. Rather than lead mankind into a world of greater harmony with God’s order (which ironically was essentially the mission statement of Babylonian kingship) they lead mankind into a state of being which facilitates the following verses in Genesis 6:

5 The Lord saw that the wickedness of man was great in the earth, and that every intention of the thoughts of his heart was only evil continually. 6 And the Lord regretted that he had made man on the earth, and it grieved him to his heart. 7 So the Lord said, “I will blot out man whom I have created from the face of the land, man and animals and creeping things and birds of the heavens, for I am sorry that I have made them.”

The result of this hybrid kingdom of mankind and rebellious gods was far from God’s plan. More than being a faulty government or culture, it was a faulty humanity which saw no feasible alternative than to do evil all the time. Remember our discussion about the Hebrew word for “evil” earlier? Ra is the word used for “evil” in verse 5 and has more to do with destructiveness or harmfulness than with our modern conception of moral evil. So, imagine a society of self-destructive individuals who’s best intentions only lead to greater degrees of death, pain, and fragmentation. This was the world under the perpendicular kingdom of giants, which as we’ll see, becomes the seedbed of what will later be called: Babel, the world, and Babylon.

Babylon and God’s Guerrilla Kingdom

However, we know that God did not just erase His creation and go back to the drawing board. What theologians call “redemptive history” began the moment God allowed for sin to be a possibility. God promised an opponent to the serpent, a “seed” or line of His own people who would stand contrary to sin and all the rulers, heavenly and human, who oppose the greater rule of YHWH God (Gen. 3:15). The logic of Genesis seems to imply that God chose not to eradicate all of mankind and start over because the odds something similar to the fall would likely happen again—but He would take a remnant of the spoiled world and grow them into His own Kingdom on earth. For this reason He selected Noah, who is described as finding “favor in the eyes of the Lord” (Gen. 6:8), and “a herald of righteousness” (2 Pet. 2:5).

Noah, like Cain, is an odd character when you consider him in context. He comes after the fall, by which we’re told all men were plunged into a vicious cycle of sin and death (Rom. 5:12). Cain is given a chance to listen to God and conquer his sin, even after the fall has happened and sin is part of his DNA. Now, again we see God speaking to one man out of all of sinful mankind to be His “seed”, from whom He plans to cultivate a new humanity. Does this mean Cain was sinless before killing Abel, and God chose Noah because he had never sinned? Not according to the rest of Scripture, which tells us transparently that every human being is born into a legacy of sin (Jer. 17:9; Ps. 51:5; Rom. 3:23). This is where we begin to see a crucial element in the development of God’s underground Kingdom in the darkened world.

Grace is a word with a lot of baggage today, and not all of it very helpful when it comes to reading Scripture. For his brevity and precision, Dallas Willard provides an excellent definition of the kind of grace we read about in Scripture:

Grace is not just about forgiveness—if we had never sinned we would still need grace! Grace is God acting in our life to do what we cannot do on our own. Grace is what we live by and the human system won’t work without it. The saint uses grace like a 747 jet burns gas on takeoff (Dallas Willard).

“Grace” or Charis in Greek, can be understood as “the divine influence upon the heart, and its reflection in the life” (Strongs G5485), and as we know, the heart is not a volitionless puppet of God’s enforcing will. As we stated earlier, the imago dei is both kingship and servanthood—freedom and responsibility. Rather the heart is the organ of our human will and is something meant to work in tandem with God’s own will.

This kind of divine energy was not only present with the coming of Christ but was present in both testaments wherever people feared and obeyed the will of God as best they knew—because God was personally moving in and through them. The illustration Willard gives of grace being fuel I have found very helpful. Human beings are endowed with a limited amount of “fuel”, and it runs out very quickly. Having God’s grace is like having a direct tap to God’s endless source of fuel. In a world which cannot merit the Kingdom of God—and it’s worth mentioning that at no point were we ever intended to merit the riches of God’s Kingdom—grace is an essential catalyst for God’s will to be done.

In the case of Noah, God saw the one man on earth with the greatest potential and poured His grace on Him. In contrast to Cain, Noah listens to the voice of God and actually does what He says. Noah listens and obeys, a theme which should not sound foreign to our ears as we read Scripture. To listen and obey God’s word is the tell-tale indicator of a heart running on grace—a seed of the woman, a remnant of the Kingdom.

So with Noah we again see a prime example of God delegating. Noah builds the ark exactly to God’s specs and God causes all the animals to board—basically a new Eden starter kit. Noah loads up his family, the flood comes and destroys the old world regime of giants, and then the flood recedes, leaving a blank canvas for God to establish His Kingdom upon. However, as you probably already guessed, this progress toward the realized Kingdom of God doesn’t last long with Noah. In Genesis 9 we find Noah planting a vineyard and getting drunk on the wine. While two of his sons have the decency to cover him up, Ham, the youngest, does something shameful to his father which is only alluded to. As a result, sin enters back into the world and from the line of Ham Nimrod is born.

Nimrod arrives on the stage abruptly and with some description. He is described as a “mighty man”, by which many scholars derive he is meant to be understood as one of the giant race, just as before the flood. Nimrod establishes a sweeping empire which becomes the seed of Babylon and Assyria, two oppressive regimes which do not leave the biblical scene until Persia in the time of the book of Ezra (Gen. 10:8–12). So, essentially, the world is back to square one, with sinful human empires governed by violent warrior giants. The world has not healed, mankind has reopened the old wound again, and we the audience are beginning to question whether God’s creation of man really was good. Are humans really able to take from the tree of life and not take from the tree that God forbids? It’s in this dark chapter of history that the Tower of Babel casts its long, dark shadow.

A Kingdom of Bricks

Genesis 11 introduces us to a new and unpresuming character: the brick. Specifically, a whole lot of bricks. As the inhabitants of the earth plot their massive building project, the language chosen about making and burning bricks suggests two crucial things: (1) no project like this had ever been attempted on this scale; this was meant to be a metropolis, and (2) their plans are not stated in prose by the writer, they are in dialogue as if one person is posing the idea to an assembly of people, what is called a “cohortative”, “….let us build ourselves a city and a tower with its top in the heavens….” (Gen. 11:4). Why is this important? For one reason: Babel is the logical conclusion of what it looks like for people to follow their own purposes over God’s purposes. It is what it looks like for all mankind to take from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil and not from the tree of life—or, in Jesus’ words, this is the broad way and not the narrow way that leads to life (Matt. 7:13–14).

In Genesis 11, the phrase, “let us make bricks” should recall the phrase, “let us make man” in Genesis 1—ironically, both man and bricks are made of the same element in the biblical creation story. Mankind at Babel is, collectively, having its own creation narrative—but this time instead of stars, seas, land, and trees, it’s creation through the humble, modular brick. Mankind is building a kingdom of its own, one it can control and manipulate independent from the will and order of God. This is punctuated by the fact that the mission statement of the city of Babel is to not do exactly what God told them to do, namely disperse over the whole earth.

3 And they said to one another, Come, let us make bricks, and burn them thoroughly. And they had brick for stone, and bitumen for mortar. 4 Then they said, Come, let us build ourselves a city and a tower with its top in the heavens, and let us make a name for ourselves, lest we be dispersed over the face of the whole earth. (Gen. 11:3–4)

It’s God’s creation of mankind, but in reverse—Babel is literally the unmaking of mankind. Here, mankind is speaking like God, using cohortative language about creating, only instead of making mankind in their own image, they are making a city in their own image, as a representative or imager of their own authority. This city, whether intentionally or not, is at odds with the will of God by confining all people to one location rather than allowing them to subdue the whole earth. Instead of following God’s intended purpose for mankind, mankind opts to turn themselves into gods, with a tower “in the heavens”, in a city where they make the rules.

However, we’re not meant to think this is just another city like the one Cain had founded. The most sinister part about this city isn’t namely its bloodshed or oppression, but something more subtle and pervasive. The Lord spells it out for us when He and His assembly come down to see what the humans are up to (Gen. 11:5–7).

Many translations make the Lord’s response to the tower of Babel almost sound like He is afraid of humanity’s growing power. I don’t think this was the intended tone of the text. When God confused the languages at Babel, it was not a move to wrench power out of humanity’s hands before they became too strong, but was more like a father wrenching a gun out of His child’s hands. God’s actions at Babel were a mercy to keep people from building structures which would steer them further and further from the tree of life—which remained God’s primary agenda for human destiny.

5 And the Lord came down to see the city and the tower, which the children of man had built. 6 And the Lord said, Behold, they are one people, and they have all one language, and this is only the beginning of what they will do. And nothing that they propose to do will now be impossible for them. (Gen. 11:5–6)

The Lord comes down, sees the manifestation of humanity’s kingdom without the King and basically says: “If they’re allowed to continue this twisted project, then nothing will stop them from implementing every other twisted idea that pops into their heads”. The Hebrew of Genesis 11:6 literally says “[then] all that they purpose to do will not be withheld from them.” But why should it be withheld from them? What was so bad about Babel?

The Never-ending Nemesis

If a modern anthropologist was given a street-level view of what it was like to live in the city of Babel, I don’t think he would be appalled. In fact, she might be impressed by how developed this ancient civilization had become and how well people got along. There are no ethnic divisions, no language barriers, no warring nations, just a city of people living together and being responsible and industrious with their resources. To a modern anthropologist it may appear like the beginnings of a future utopia, freed from the troublesome barriers of separation and division geopolitics wrestles with today. So why did God decide to kick the ant-mound and ruin this potential human utopia? We might also ask in the same train of thought why Jesus didn’t come down to establish an empire to rival Rome. They are one in the same question, and the answer is more unsettling than many, including well meaning Christians today, are willing to admit. God’s Kingdom is not made of bricks.

Remember my upside-down pyramid analogy from chapter 4, how around the base of the enormous pyramid there were huge hulks of bricks laying strewn all over the ground? This is where human systems have tried to append themselves to the eternal Kingdom of God and have been proven incompatible. The Kingdom of God isn’t that sort of thing. “Your kingdom is an everlasting kingdom [Heb. a kingdom of all ages], and your dominion endures throughout all generations.” (Ps. 145:13). Various Babels rise and fall with the regularity of the tide, but God’s Kingdom was there in the beginning, the unmoved mover. The moment there was order from God’s will, there was the Kingdom of God, and that isn’t the case where human wills are in charge of ordering.

Nothing differs more from Babel than the place where God’s rule and reign is present. While they are both systems into which human beings are designed to fit, the crucial difference is one has the tree of life and the other leads to death—one is oriented around the will of God being done on earth as it is in heaven, and the other is bent on having human will done regardless of what heaven has to say about earth. When earth ignores heaven, there is little it can do to save itself.

Imagine if the planet earth were given a free will which would allow it to decide to ignore its orbit around the sun. It would be a free act to leave, but no matter which way it went all life on earth will cease. It’s the same with mankind in the order God has prescribed for creation. The moment anyone does anything contrary to the will of God, that act makes the one who willed it out of step with true reality, which naturally leads to separation from the life-giving center of reality. To prevent this death in the distorted kingdom of mankind, God kicks the ant mound, and really makes a habit of doing it.

As you continue to read through your Old Testament you’ll realize just how common this thread is. God is unwilling to compromise with brick structures which pretend to do His job for Him. The moment you think mankind has risen to its high calling, God scatters them and confuses their language. The moment you think God’s built a sustainable empire on earth, He sends it into exile in Babylon. The moment the Messiah, the promised conqueror and king of the Kingdom, comes He turns out to be humble, meak, and obedient even to the point of death, crucified by the government. The moment you think the risen King is going to stay and build His new empire, He leaves it in the hands of His Church for thousands of years. He purposefully breaks down our structures and Babel-inspired expectations to turn people back to Himself, the only real source of life.

To our eyes, there could be no messier or more impractical way to build a Kingdom than the way God seems to be going about it. But this just illustrates the point. The reason we see God’s way as messy and even foolish sometimes isn’t because we actually know better than God, but because we ourselves have Babel-soaked eyes. Babel didn’t just stop after God confused their languages and scattered the nations. Babel is the archetype of all human structures built on humanity’s understanding of the knowledge of good and evil without God. They don’t even need to be excessively arrogant structures to be manifestations of Babel, they simply have to operate off of human wisdom and not God’s. Empires, nations, corporations, even families and churches can be built on the foundations of Babel, completely absent of the life of God which only comes to human souls in His Kingdom.

We live in Babylon just as much today as in the book of Daniel. But, as we’ll soon see, that doesn’t mean we have to be Babelonians. Just because the reality we’re presented with compels us to sell out and buy into the babylonian dream doesn’t mean it’s true. We’re told time and again in scripture that Babylon will one day be out of ground to stand on, and in its place will stand the absolute and undeniable Kingdom of God (Dan. 7:14; Jer. 51:55; Rev. 14:8).

But what about this in between space? Scripture is clear, in Christ we are no longer citizens of Babylon, we’re pure imagers of His Kingdom (Col. 1:13); and since we’re no longer affiliated with Babylon we are to “Take no part in the unfruitful works of darkness, but instead expose them” (Eph. 5:11). This means we must live a new life, inside and out, which reflects a reality Babylon cannot accept as true without accepting God as the ruler of reality. The citizen of the Kingdom of God shares the will of God, and as we know from Scripture, God’s will makes no treaties or compromises with Babylon. As crazy as it sounds to “earth-dwellers”, we are expected to live as though the Kingdom of God is now as well as coming. We are expected to live against the stream of Babylon (Rev. 18:4) until the whole earth is filled with the knowledge of the glory of God as the waters cover the sea (Hab. 2:14).

But how is it possible for this reality to be both “now and not yet”, as theologian George Ladd has coined it? Interestingly, it’s not as mind-bending as you’d think. As we’ll see in the next chapter, the overlapping of heaven and earth is key to the Scriptural understanding of God’s eternal Kingdom with human participation.

The Ghosts of Cloudy’s Forest

The Ghosts of Cloudy’s Forest